Back to the news list

Back to the news list

Oman has weathered all the innumerable challenges of 2020 with considerable flair, even though the year started off with the untimely passing of Sultan Qaboos, then came the coronavirus pandemic and the renewal of OPEC+ production curtailments that have dealt the economy the double whammy of lower prices and lower production. The Middle Eastern nation is now trying to grapple with the second wave of COVID, adapting to a new way of life under curfew and under increasing fiscal pressure. Whilst much of this year brought no big new on Oman’s oil, its gas segment might be taking over the relay baton as the case of the giant Ghazeer field demonstrates. Oman has heretofore been consistent in its OPEC+ commitments, sticking to the 682kbpd production quota it had agreed to. Under normal circumstances Oman’s output would have been around 930-950kbpd yet difficult times necessitate difficult decisions. Hence, the 947kbpd rate of production in April 2020 dropped to 679kbpd in May 2020 and has more or less stayed at that level since. The main thrust of the production cut fell on Block 06, operated by Petroleum Development Oman which is partially in the state’s hands. Of the 201kbpd additional production cut that Oman committed to, 135kbpd is from Block 06 and Occidental Petroleum acquiesced to drop output by 58kbpd from its Blocks 53, 27 and 09. Although a testament to Oman’s flexibility vis-à-vis declining demand (despite not being an OPEC member), the country’s 2020 budget assumed that monthly production levels would hover around 965kbpd.

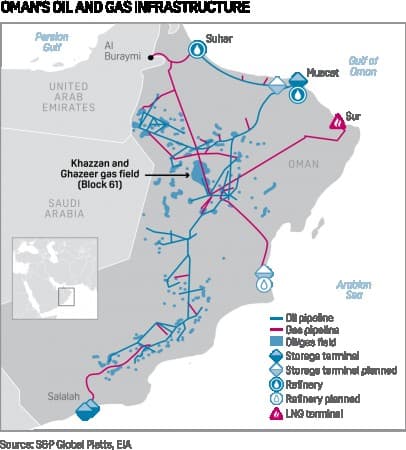

Graph 1. Oman’s Oil and Gas Infrastructure

On a national level, Oman has taken resolute measures to make its political presence leaner and more adaptable. Mohammed bin Hamad al-Rumhy who has led the sultanate’s energy ministry for 23 years already, has seen his influence increase as his office was extended iOne of the most obvious ways to put a spin on Oman’s hydrocarbon production would be to examine its offshore areas more closely (and actively). Despite being an oil exporter for more than 6 decades, Oman’s heretofore only notable offshore project was the Bukha field – it produced some 285 BCf over the course of its 25 years’ production. The Bukha-Henjam field was located on the Omani-Iranian maritime boundary and was developed according to the frontier split; all of Oman’s production went to the UAE as the field itself was connected to the Emirati port of Khor Khwair by a 35km subsea pipeline. As Bukha entered terminal decline, there remained little to look forward to, despite oft-repeated claims that the Strait of Hormuz could unearth several major discoveries.

On the back of Oman’s onshore oil production maturing, Muscat was looking forward to 2020 as the year when it could finally boast of sizeable offshore discoveries. Reality, however, turned out to be much less inclined to daydreaming – more than 100 exploration wells were drilled in 2019 yet only one of them was spudded in the country’s offshore. Of the 6 seismic surveys conducted last year, once again, just one was offshore. Anticipation is great, however, regarding offshore drilling on the back of media rumors spinning ENI’s Fanar-1 exploration well as a harbinger of offshore discoveries to come (even though the well’s official results are still yet to be issued). What 2020 did provide was a major gas breakthrough – not an entirely unexpected one as Ghazeer’s launch was planned for 2021 yet certainly one that deserves a special mention. The commissioning of the Ghazeer project 4 months ahead of schedule might become a harbinger of good things to come, namely that Oman’s gas projects will mitigate the effects of oil stagnation. Ghazeer constitutes the 2nd phase of the giant Khazzan-Makarem gas field, one of the top tight gas development in the Persian Gulf region. The total proven reserves of Khazzan-Makarem stand at 100 TCf (2.8 TCm), although the recoverable reserves tally will very much depend on how BP, the project’s operator, will technologically manage to extract tight gas from the Ordovician to Proterozoic deposits. Phase 1 of Khazzan-Makarem started almost exactly 3 years ago amid intense horizontal drilling (an estimated 90% of the 300 wells assumed to be drilled in Block 61 will be horizontal, BP claims), taking the field’s gas production to almost 1 BCf/day. nto a new Ministry of Energy and Minerals. The anticipated 2020 IPO of OQ (the successor of Oman Oil, named after the deceased monarch), whereby the Omani national oil company would have become the second Gulf NOC to list its shares (not all though, 20-25% according to preliminary plans), was taken from the actual agenda as there seems to be very little probability Muscat can carry it out adequately given the current circumstances.

Following BP’s statement that it has received first gas from Ghazeer on October 12, it is to be expected that Block 61 will soon reach 1.5 BCf per day (42 MCm per day) threshold that was presupposed for the 2nd phase of Khazzan-Makarem, i.e. more or less a third of Oman’s gas consumption under normal, non-COVID, circumstances. In terms of its electricity generation, Oman remains a heavily gas-dependent economy as natural gas amounts to 90% of total production. Additional gas output should not be a problem for the economy to digest – first of all, Oman can finally get rid of oil as part of its electricity generation matrix and can easily cushion the 30-40% hike in electricity demand that is forecasted to take place by 2025. Considering that the national oil company OQ holds a 30-percent stake in Khazzan-Mukarem, the field’s prolific ramp-up is also good news ahead of the anticipated IPO.

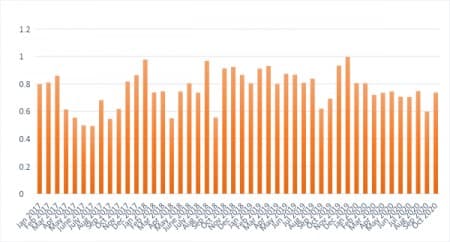

Graph 2. Oman’s LNG Exports in 2017-2020 (in million tons LNG).

Ghazeer has been beneficial to Oman in two additional ways. Firstly, it contains not only gas but also condensate which is not capped under the OPEC+ agreements, allowing Oman to hike condensate output to an all-time high of 220kbpd this summer. Second, Ghazeer might be a feedstock source for any further increase in LNG export capacity. The first phase of the field has already allowed Oman LNG to finally use the liquefaction plant up to its technical capabilities and work all three trains (3.3mtpa, 3.3mtpa and 3.7mtpa respectively) simultaneously, a feat that one can easily deduce when assessing Oman’s recent LNG exports (see Graph 2). With the current LNG supply glut this might not seem the most interesting proposition, yet it will be a great-to-have option to wield should the Asian market dynamics change.

Không thể sao chép